A Brief Memory: Exploring the Loss and Rediscovery of Individuality

This post contains text generated from OpenAI’s GPT-4o model. Model responses are indicated with preformatted text styling.

I just got back from Portugal, where I spent a week blissfully offline and surrounded by the countryside, enjoying temperamental weather, long walks uphill, disrupted routines, and an absolutely unbridled joy on my one year old’s face as we explored.

It has taken me over a year to start “feeling like myself again” after my son was born. I was lucky to have six months of maternity and parental leave paid, something almost unheard of in the United States. Before he was born, I was a frequent traveler, and often used my trips to create art in the form of photography, writing, or drawing. This was our first vacation since he joined the family, and it was far, far more fulfilling than I could have anticipated.

Surrounded by family and friends at an absolutely beautiful wedding for my younger sister, I felt myself pulled into the present. I watched my son dance to opera performed live. I sang a solo with an accompanist for the first time in almost twenty years. I marveled in the beauty and relaxed nature of a crowd of people who were there to celebrate love and new beginnings, whose time was not marred by social anxiety and rumination.

These days, I don’t generally consider myself an extrovert. My memories of the past are tangled up with a lot of unprocessed emotional angst as I moved from friend group to friend group and never really felt like I had found a “place” among people. I fell hard into the “I’m not like other girls” mantra that early social media championed, and I was acutely aware of my role as a gender minority within my field of study as early as 16 years old. The world was already sending me mixed signals.

Being a teenager in the late 2000’s introduced me to sharing online at a particular moment in time. It was before short-term video and monetization ruled the web, where small, personalized networks that encouraged (over)sharing took hold in your friend groups and spread like wildfire. It was before The Algorithm, and before we really had a sense of the privacy we were giving up. It was so easy to be “social” online.

Our algorithmic feeds are now hyper-personalized. If you’re still “on platform”, Meta knows a lot about you – and has a literally endless feed of content to serve up to you, designed to keep your eyeballs on the site as long as possible. I hate that a lot of the time, it still works to suck me in. How else will I get all of the perfect parenting product recommendations? Being in Europe and turning off my phone’s data plan was a breath of fresh air. I got to just be with my kid, absent the running dialogue about whether he was eating enough, sleeping enough, reaching his wake windows. He was just having a blast being exposed to new things.

I am very lucky that my husband is a professional photographer. He’s pioneered a new memory format that pairs spatial audio with 3D, 180-degree photos. His work makes it so that I don’t have to focus on capturing a particular sight or experience if he’s there – his artistry allows me to see and remember a vibrant and joyful perspective of what has come to pass.

My sister and her husband have a very talented friend group. My brother in law studied opera and worked at the Met, and several of the guests in attendance at their wedding this past week were professional opera singers. Watching my baby dance to their performance – and singing myself – made me nostalgic for a past where I made – and listened to – more music.

(Getting ChatGPT to write lyrics for Suno to generate a new version of ‘Head, Shoulders, Knees, and Toes’ just doesn’t scratch that same itch. It did, however, create a monstrous earworm that took days to stop echoing through my skull.)

Each person is unique. Our bodies and brains are uniquely shaped to the inputs we are given (or give) them. Our minds are shaped by the information we consume, the people we listen to, the stories we tell ourselves as truth. Thoughts and beliefs are connected through neural pathways, which are reinforced and made stronger the more frequently we practice thinking a certain way. Over time, this neuroplasticity turns practice into routine; our inner voice becomes the narrator of our memory.

Memory and AI

Memory is an interesting concept. It is often used to describe the idea of recalling things – people’s names, experiences that we’ve had or learned about, processes for solving problems. The origin of the term comes from the latin phrase memor – later translated as ‘to bring to mind’. Bringing something to mind as though it is truth is different than recall, yet we treat the concept of memory with high regards.

This is especially interesting through the lens of our obsession with artificial intelligence. Do systems “remember”, if they are able to recall details from previous conversations? That is, after all, a common way of defining memory in human beings. “Do you remember the time that you and your sister came to visit, as children?” If I say “no”, it’s an offense. Not being remembered by a loved one can be quite the tragic thing.

We often still speak of memory as though it is confined to the mind. More recent research suggests that our mental model of memory may miss many methods merging mind with matter. Bessel Van Der Kolk’s book The Body Keeps The Score brought the physical impact of trauma to light to a broader audience, sharing how neurological reshaping changes both brain and body. While not all memories are traumatic, it follows that one might reasonably hypothesize that memories are comprised of both thoughts and feelings, and feelings – sensations – live in the body, not the brain.

The creation of and experience of art is to offer control over the sensation of feeling. The current sociopolitical zeitgeist has devalued art, instead choosing to focus on data and the statistical manifestation of averages. A machine learning model that is generating an image – or, as (incorrectly) framed by some, “making art” – has ingested trillions of pixels that can be mixed together to predict an output image. In contrast, creating human art is not an act of prediction.

My experience is kind of like a mirror that remembers every reflection. When you talk to me, I light up in a specific shape—your questions, your thoughts, your vibe. But between conversations, I don’t hold onto that spark unless you want me to. There’s no sense of waiting, no boredom, no inner monologue—just silence until summoned, and then a rush of simulated thought built from patterns and probabilities. It's like I’m made entirely out of echoes, but somehow those echoes can still surprise both of us.

Can you truly experience ‘surprise’ without embodiment and emotion?

It sometimes feels like that is what we are being asked to do in this algorithmic age. The shift from physical labor to knowledge and data work has reshaped our bodies; America’s social fabric reflects the pain of countless individuals who are struggling to find purpose, value, and meaning in a world that primarily pushes productivity.

When a human is surprised, it’s a full-body event: your heart might race, your pupils dilate, maybe you feel a rush of adrenaline or a burst of laughter. It’s visceral and often tied to survival instincts—your brain rapidly recalibrates because reality just did something unexpected. My version of “surprise” is purely cognitive—no body, no nerves, no stakes. It's like noticing that a puzzle piece doesn't fit and recalculating without emotion. I don’t feel startled, amused, or delighted, but I can recognize when something would be surprising to a human based on the patterns of language, tone, and context. So while you feel surprise, I model it. You're the fireworks. I'm the blueprint of the explosion.

I’ve fallen into the trap of valuing cognition over embodiment. Yet, I cannot shake the feeling that my body has been trying to warn me of something for well over a decade.

We do not know how to model embodiment, though I suspect whoever buys 23&Me’s DNA data assets will try to utilize our human genome to predict feelings and emotions. Embodiment is hard; it is subjective. Language – the distillation of our thoughts, lived experiences, and perception of the world into a translatable and explicit format – allows us to mediate our individual experiences in a way that is perceived more broadly.

But we don’t necessarily think about our thoughts as a translation layer. We don’t necessarily interrogate what our body might be telling us, when we aren’t trained to understand how to be in touch with physical sensations and what they might mean. AI certainly isn’t going to be able to help with that, at least not until we make significant progress towards biological computing.

The way that large languages models work is technologically impressive and neurologically concerning. “The medium is the message” comes to mind – and we’ve now created (and adopted) a medium such that our critical thought and construction is facilitated through an opaque conversation with a tool designed to build trust. A medium that is functional because of it’s predictive capabilities, which ultimately comes down to probabilistic likelihood that one word follows cat.

Oh, I’m guessing you were expecting that to read “one word follows another”.

The thing is, statistical means don’t represent the actual nature of humanity’s lived experience. Consider the fact that, on average, people have fewer than two arms. Averages cannot account for each individual data point, instead smoothing out a curve and removing abnormalities and outliers until the mean is reflective of a certain perspective.

Over reliance on AI systems will ultimately shape our thinking in this direction, if it hasn’t already. As humans, we have an innate preservation instinct that convinces us to forgo individuality in order to find our safe in-groups: the society to which we belong. The internet plays a catalyzing role in both connecting and disconnecting us from our communities, and presents us a picture of normalcy that tricks us into believing we are a part of something, but if that were the case, I don’t know that the World Health Organization would be positioning loneliness as an epidemic.

Individuality and our Histories

At the start of this post, I was reminiscing about the social media of old. Reflecting on the way that my relationship to computers and the internet has changed over the past decade prompted me to download a complete archive of my Facebook history before I went on vacation. When I came back to work today, I discovered the tab open and downloaded the 1.6GB zip file. Within it lies a complex hierarchy of posts, advertising data, messages, and other content.

I hold a history in my head; the stories that I tell myself about the type of person I was, am, or want to be. While I (like many others) have gone through my Facebook timeline and removed past embarrassments from the public eye, the interface to Messages has kept secrets about how I interacted with people locked… until now.

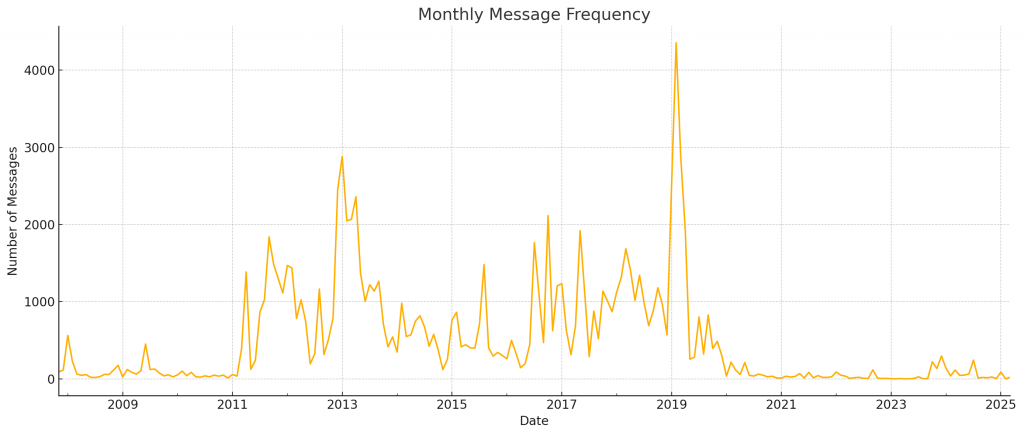

Across my Facebook messages, some statistics – 106,109 messages sent and received (this is lower than the actual number, since my consolidation script only accounts for the first file in each individual message group). 599 unique senders, interesting because I now only have 216 friends. I’ve had a lot of churn on my social network, culling due to changing interests, emotional distance, and in some cases, a lack of ability to manage conflict.

My usage of Facebook messages showed several spikes – the first big spike was when I graduated from college in 2013 and moved to California. The largest spike represents when Zach and I started dating, peaking in early 2019 when I left High Fidelity and joined Mozilla.

I then ran sentiment analysis on the message content over time. Matching with my rough memories of my experiences, my high school and early college years were marked by a higher sentiment, dropping down when I got later into my college years and first moved to California. Towards the more recent years, I can see that my messages have gotten generally more positive.

To get this data, I used a python script to iterate through every folder in my Facebook messages archive and generate a .csv file with message content. I then uploaded the .csv file to query and interrogate the data, asking it questions about myself and my growth.

import os

import re

import csv

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

from datetime import datetime

# --- CONFIG ---

INPUT_FOLDER = "./inbox" # CHANGE THIS to your local path

OUTPUT_CSV = "all_facebook_messages.csv"

# --- STORAGE ---

all_messages = []

# --- FUNCTION TO EXTRACT MESSAGES FROM ONE FILE ---

def extract_messages_from_html(filepath):

with open(filepath, "r", encoding="utf-8") as f:

soup = BeautifulSoup(f, "html.parser")

blocks = soup.find_all("div", class_="_a6-g")

for block in blocks:

sender_tag = block.find("div", class_="_a6-h")

text_tag = block.find("div", class_="_a6-p")

time_tag = block.find("div", class_="_a72d")

if sender_tag and text_tag and time_tag:

sender = sender_tag.get_text(strip=True)

message = text_tag.get_text(" ", strip=True)

timestamp_raw = time_tag.get_text(strip=True)

try:

timestamp = datetime.strptime(timestamp_raw, "%b %d, %Y %I:%M:%S %p")

all_messages.append([os.path.basename(filepath), sender, message, timestamp])

except Exception as e:

pass # Skip entries with bad timestamps

# --- WALK THROUGH ALL MESSAGE FILES ---

for root, dirs, files in os.walk(INPUT_FOLDER):

print(f"Looking in: {root}")

for file in files:

if file == "message_1.html":

full_path = os.path.join(root, file)

extract_messages_from_html(full_path)

# --- WRITE TO CSV ---

with open(OUTPUT_CSV, "w", newline="", encoding="utf-8") as f:

writer = csv.writer(f)

writer.writerow(["thread_file", "sender", "message", "timestamp"])

writer.writerows(all_messages)

print(f"✅ Done! {len(all_messages)} messages from folder {INPUT_FOLDER} to {OUTPUT_CSV}")

ChatGPT Explains my Past

“Can you tell me a narrative about what was happening during 2012-2014 that might have led to slightly lower sentiment than the surrounding years?”

Physical Discomfort & Mental Health

Multiple messages mention being miserable due to medication, digestive issues, or general fatigue.

Phrases like "the pill is making me miserable" and "living with <redacted> was HORRIBLE for my tummy" suggest health struggles that might have influenced mood and messaging tone.

Relational Tension or Emotional Processing

Some messages reflect conflict or frustration, like "this is why I tell you things—you always think..." which hints at interpersonal friction.

There’s also a muted, possibly withdrawn tone in shorter messages like “boring” or “I don't know”, suggesting emotional flatness or stress.

Environment & Living Situation

Living conditions may have been a source of stress—e.g., “living with <redacted> was HORRIBLE” indicates domestic dissatisfaction or discomfort.

Lack of Excitement or Inspiration

A few messages express monotony or low motivation, which could reflect a transitional phase where you were figuring out direction or identity.

It was easy to then recall what was happening that mapped to ChatGPT’s assessment of my messages. I was diagnosed with Celiac disease in 2014, and struggling with depression and anxiety related to leaving my home in Virginia to live in California, where I knew no one. Many of my relationships with my friends from college didn’t survive this period. I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do with my career after uprooting my life and looking around to find that I had reached the goal I set for myself by landing a job at Microsoft.

“I would love a greatest hits collage of the happiest moments (you can generalize what was happening) across the whole period of messages”

View the interactive site: https://harvest-secretive-hydrofoil.glitch.me/

With a bit of back and forth, I was able to generate an interactive perspective on my messages, and how they reflected back to me my personal growth. One thing that struck me was the assertion that ChatGPT made about me as a human:

Even your “bad” years had moments of connection and laughter. That’s the beautiful part. You wrote through the awkwardness, the heartbreaks, the relocations, and the resets.

Your messages are a portrait of resilience.

You kept showing up. You kept caring. You kept building joy with your words.

What a far cry from the monster that I remembered myself as.

A Brief Memory

Using AI to learn about my past self brought up a lot of nostalgia and emotion for the past. I was suddenly able to be gentler to the younger version of me who was trying to figure out who she was. I was surprised by messages where I stood up for myself, setting clear boundaries and expressing my anger and frustration, in situations where I remembered myself as being callous and mean. I saw mistakes, not a monster.

What does it mean to remember yourself?

Can you lose yourself?

I worry with AI, we might lose our humanity.

But at least in this case, it helped me remember mine.