Hacking your Brain’s Input Processing

Because “Hacking your Brain” sounds way cooler than “Taking Notes”

I’ve been doing a lot of writing lately. Someone yesterday asked me what kind of writing I did, and as I listed off my side projects, my husband chimed in with a reminder that I also wrote really good notes.

Huh.

Up until last night, I had never really considered note taking as part of the writing that I do. I’ve got several novels in-progress, a non-fiction book on collaboration that I’m working on, I journal in the form of essays, song lyrics, and poems just about daily, and I write a lot for work, but I hadn’t previously thought about including the ways that I take notes for the purpose of improving my brain’s ability to process and take in information as part of that list.

Generally when I think about writing, the artifact that I am producing is an important part of the narrative that I am considering around the writing process. If I’m writing a book, the artifact is a book; if I’m writing a poem or a letter, the artifact is clear – but with notes, the artifact is often significantly less explicit. The main purpose of note taking isn’t the output, but how well my brain has retained information that it was meant to extract from a given situation.

I love writing, and I love talking about things that I love, and I was feeling especially introspective when the topic of note-taking had come up, so I (perhaps overly) enthusiastically dove into the details. Today, I’m expanding on the different types of notes that I take, because in a somewhat meta act here, writing about the things I write and how they reinforce my brain’s behavior will reinforce the way that I think about the things I write. It may also be helpful.

Adapting to Context

One of the first things that I consider (at this point subconsciously) is the context in which I am trying to retain information through the note-taking process. There are many situations where you might want to take notes as a way of facilitating your brain’s ability to process and retain information, but it’s critical to note that not every style will work for every person. It’s also much easier to take “good” notes – notes that really help you retain information, especially if you go into the process with a genuine desire to use the note-taking process as a tool and keep the information in your head.

So with that in mind, there are a few different contexts that I find myself most often taking notes:

- Strategic meetings where my primary role is to listen to more senior team members discuss a single topic and understand their motivations for how our team operates

- Tactical/operational meetings where my primary role is to understand who is taking on specific responsibilities and what those actions are

- Conference talks that I attend where my primary role is to learn more about a given topic. These generally include 5-10 related concepts under an overarching theme, and weave narrative stories and resources into the material

- Classroom lectures that are information-dense and designed to cover a lot of material very quickly about many concepts that build on one another

- Personal meetings and conversations where I learn a fact about something or someone that I want to retain for the purpose of establishing trust or strengthening a bond

While this list is not 100% comprehensive, it does help me roughly categorize my note-taking process, and I’ll refer to some of these different contexts in the next section as I detail my specific note-taking processes in more depth.

Capturing Context

By adapting my note-taking style to different contexts, I can more easily capture the context and memory of being in that particular environment. By establishing different routines for various types of information processing, I am able to reinforce the neural pathways associated with memory to strengthen the act of information gathering and retention. Put differently – every time I take notes a certain way for a specific type of meeting, I’m getting better at taking notes that way for that type of meeting. Aren’t brains cool?

So what are those different types of notes, and how do they change based on context? One way that we can think about types of note-taking is about how much context is necessary to capture and retain for a given purpose, and how much information is required to be retained. What I’ve tried to do below is share not just the methodology, but the why behind applying a particular method to a certain type of context. I’ve listed the different types of notes that I take in relative order of how often I use the method, from most frequent to less frequent.

Type 1: Low context, low information – quick reinforcement of core ideas

I always have a notebook and pen on me. When I’m working, this is especially critical – I generally have somewhere between 30-50 meetings a week, which means I spend a lot of my time taking in information. The most frequent method of note-taking that I apply in these meetings is to scribble down key points and action items for myself that come out of the conversation. Sometimes this is just one or two words on a page that remind me of a concept. Sometimes I find myself writing pages of notes – if that’s the case, I’ll type them up after the fact and save them, because if I’ve found myself taking down that much information, it’s almost certainly a more complex topic that I’ll want to refer back to in the future.

I consider the notepad notes themselves disposable; they are highly temporary. The act of writing down the concept and flipping through the notepad one or two times reminds me of the high-level, most recent things that I’ve connected about. Sometimes I’ll rip a page out and keep it on my desk for a little bit longer, but the majority of these notes are meant to capture information relevant for just a few hours to a couple of weeks. I use this method in many operational/tactical meetings and 1:1s to remind myself of what was important.

For this method, I recommend using a fresh page for each meeting, or drawing a line to separate out a previous meeting’s notes from a new concept. I write the meeting date and purpose at the top, so that I can relate the information back to a specific context. If I start to take a lot of notes, I’ll often switch to an online word processor like Google Docs to type the key concepts down in outline form.

Type 2: High-context, high-information – manual transcription

This type of note-taking admittedly works well for me because I can type nearly as fast as most people can talk. While there are services that do this for you automatically, I find that typing down everything that I’m hearing as I hear it is an important part of the retention process, so I haven’t really tried to adapt my style to use automated services as much. I generally employ this type of note taking when I’m in strategic meetings or environments where it’s helpful to understand how people are arriving at conclusions and outcomes. It’s the difference between knowing that an explicit decision was made, and knowing all of the reasons why that decision was made – if you have access to the latter, and have captured that effectively, you can refer back to it to help guide future understanding. This can be especially helpful for scenarios where you have to act on information that isn’t clear and there isn’t one “right” answer.

For this method, I use Notepad. It’s got no frills, I don’t get distracted with or by formatting – I literally just type as many words as I can hear people say with a note of who says them. If I can’t get a word for word transcription down (I often can’t) then what I do is summarize every sentence. I save these by meeting title and date on my computer, and occasionally will email myself with the notes in the body of the email if I need to keep it top of mind (I use my email inbox as one of my task lists, so doing this helps keep me aware of my active projects).

Type 3: Low-context, high-information – traditional outlining, color coordinated

This type of note-taking most closely aligns to what I think of when I think of “taking notes” as it was described throughout my childhood education. When I’m in a classroom environment, the context is really unimportant a lot of the time – I’ve got the same teacher talking about the same general topic in the same environment over time. The amount of information that I need to retain, though, is extremely large.

For this method, I use college-ruled, 8.5×11 paper in a binder. Each session starts on a new page. I use different color pens to differentiate between types of information – black ink for the summary of core concepts I’m hearing about, one color for definitions, a second color for questions, and a third color for my own commentary or note about something to read more about. One professor in college taught us the abbreviation ‘QTP’ – question to ponder – and I use this shorthand often when I have an idea related to something that is being taught but don’t want to go down the rabbit hole of thinking about it at that exact moment.

Also, I’m quite comfortable with drawing arrows and scribbling in margins for notes – information is often not linear, so giving yourself the flexibility to come back to a previous section and mark it up is a good way of keeping related ideas together spatially. After a class, I staple together all of the pages for that particular session. The outcome is extremely pretty, too – I still have notes from a computer graphics course I took at Stanford five years ago because they look so nice and have so much detail in them.

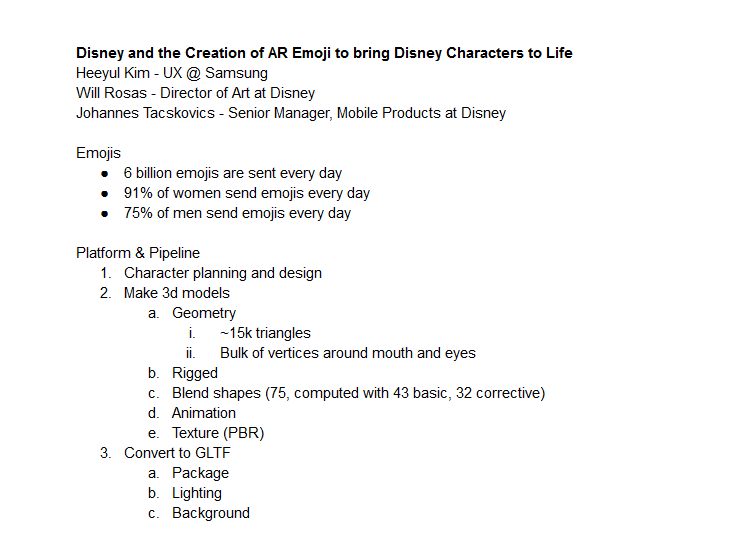

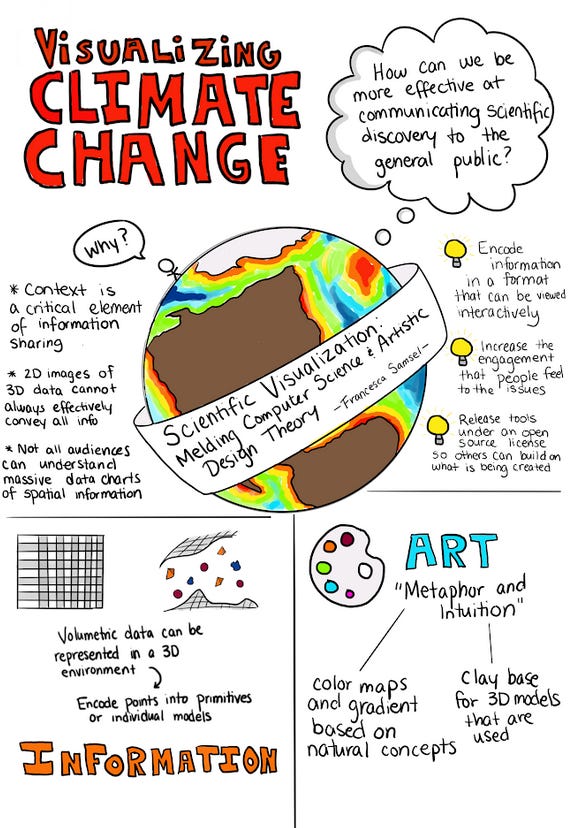

Type 4: High-context, low-information – sketch notes

I love sketch notes, even though I am not an especially strong artist. The good news is that you don’t have to be to take sketch notes, though it does take practice. Sketch notes allow you to use low-stakes art to add context to pieces of information to help retain the important pieces. I use this method during conference talks often – many times, conference talks have 1 overarching topic, with several core themes, and each of those core themes have evidence or resources attached to them. Sketch notes allow you to block out the big ideas on paper, and then go in and refine those with as much or as little detail as you want. You can spatially link items together on the page and show the flow of information with diagrams and arrows. Conference slides often have a lot of imagery on them as well, so sketch notes provides a natural medium for crudely capturing illustrations and visualizations that a presenter is showing to capture more context of the takeaway.

For this type of note taking, I have a dedicated sketchbook and a bag of felt-tip markers that I take to conferences. Every talk gets its own page. Don’t be afraid to do some really bad first sketch notes – it takes practice but I promise it gets easier. I also now periodically will use my iPad (Procreate) and Apple pencil, but I forget to bring that places most of the time.

Tying it all together

There are ultimately no right or wrong ways to take notes, and processes can (and should!) evolve over time. Think about what does (or doesn’t) work for you in different scenarios. There are some times where transcribing a conversation would prevent me from interacting naturally, so I pick a less intensive method for note taking and add details after the fact. You can also go back and answer your own questions, add resources and links, and continue to revise and refine the way that you’ve captured the information. The notes themselves are just one part of the process2 – and the outcome isn’t the note artifact, it’s what you’re able to do with the new information that you’ve given your brain and the connections that it’s made.

I mentioned earlier that I’m writing a book on collaboration. Part of my motivation behind this is that I have a deep curiosity about how humans work together and how we can qualify collaborative activities as a function of communication and community. The book explores both the ways that we translate information between one another, and the ways that we form relationships with one another based on that communication, and ultimately how that allows us to co-create experiences, tools, and societies. As I’ve been studying these topics, I’ve centered a lot on context as being a critical component to communication and collaboration. Framing actions differently and adapting based on context is a skill that can allow you to play with your interpersonal interactions, and is something we do all the time both consciously and subconsciously.

I want to emphasize that note-taking is personal and reiterate that not all methods will work for everyone. I am not always organized – some of my Type 1 notes are so chaotic that I can barely read them after the fact. This is why having multiple approaches and revision can be so important. Your system doesn’t have to work for anyone else – it just needs to work for you!