The Archivist Within

Twitter played a significant community role for me when I first started out in my career. Over the course of several years working in developer relations at Microsoft, focused on virtual and augmented reality, I developed a strong network of people who regularly engaged with my work (and I theirs) in a frequent and low-stakes manner. It was a (relatively) safe way to interact with people in an extended field, and I made several close friends on the platform whose work continues to influence me today.

I had joined Twitter in 2011 as The Girl Who Plays Wow, a moniker I went by when I still ran a World of Warcraft blog and struggled to separate my AFK identity from the Night Elf Fury Warrior who had high opinions of herself. When Aistra fell in love with her Guild Master, our relationship carried over to my sophomore year of college and I followed him from Azeroth to the mystical online land where the only game was to share 140-character updates about not sleeping, hard Computer Science exams, and what I ate for lunch that day.

That relationship (and Twitter handle) didn’t last, but my interest in the growing social media site did, and over the course of 11 years, I had nearly 20,000 people reading my updates, which had shifted in topic from my sorority events to the expansive shifts happening in computing as AI and XR entered the chat.

When Elon Musk purchased Twitter in 2022, I archived my tweet history and crafted a personal CRM of the people I followed on the platform before closing the account. It was a difficult decision – for someone Chronically Online, who had built an immense amount of professional capital (and personal relationships) from the site, losing an entire network of tens of thousands of people overnight was lonely.

Shortly after archiving my Twitter accounts, I made the decision to move off of Windows. In the subsequent operating system installs that followed, I lost my Twitter archive. Digging through old HDDs and SSDs and recovering corrupted data proved fruitless, and after years of searching, I accepted that the entire record of my time on Twitter was permanently gone.

I’ve written before about how I’m building a personal data archive from my social media posts and messages, but the Data Introspection Project took a brief hiatus over the summer after I joined the team building Mozilla Data Collective. As it turns out, my interests in reclaiming my data is part of a larger shift happening, and communities are increasingly taking a collective approach to data stewardship and governance as an antidote to Big Tech’s data heist. It’s painting a far more optimistic picture for what the future of equitable AI and machine learning can be.

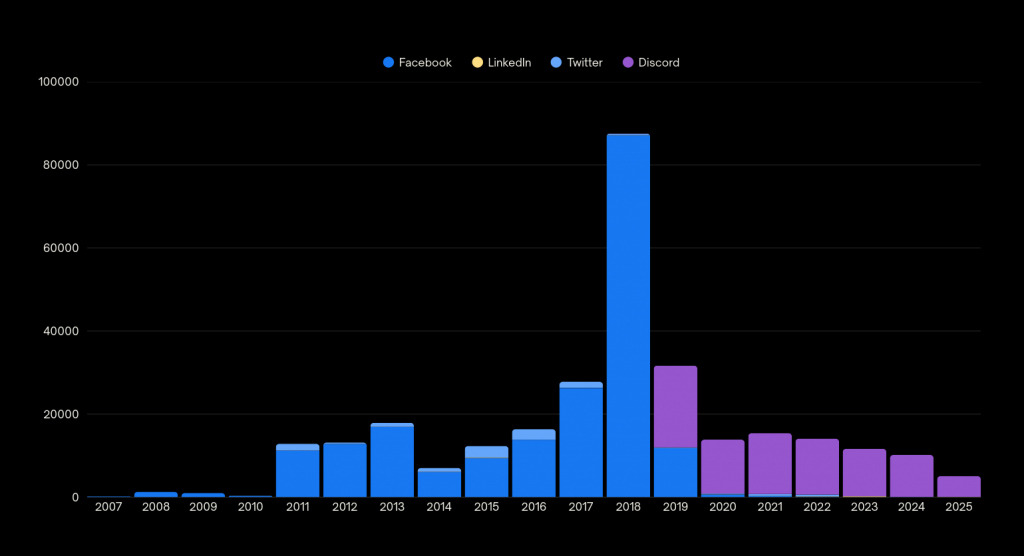

As part of my journey to use analytics and data for my own personal sociological, psychological, and philosophic interests into the concept of the self, I’ve been building a personal data archive. As of today, the sqlite database has 299,970 entries spanning 18 years of content and 4 social media platforms.

Yes, four – because today, I found my Twitter archive.

Preparing 12,000+ tweets for my archive database was straightforward. With the help of ChatGPT, I wrote a script to parse through the tweets.js file and extract every tweet, alongside the month and year that the tweet was posted. These were saved to a .csv file, which I then cleaned manually to fix any issues with parsing (my script did not handle character encodings well, and past-Liv used a lot of emoticons) before importing it into the database.

sqlite> select message, year, month from content where platform like 'Twitter' limit 10;

MESSAGE|YEAR|MONTH

Because software and VR are amazing <3 #ILookLikeAnEngineer http://t.co/CGYAAU3wvO|2015|8

RT @kentbye: Awesome insights & innovation by @kertgartner for why VR trailers (& VR streams) really need to be in 3rd person POV https://t…|2016|12

Alcohol is basically using <b> tags on your personality.|2016|6

@MicrosoftHelps It's the link on http://t.co/8neNowZjnS -How it works - Download the planning guide (on the side bar)|2014|5

RT @kentbye: UNC's Mary Whitton is a pioneer of graphics & #VR & covers her fundamental research on locomotion & presence @RENCI https://t.…|2016|12

@inannamute >.> But... I ate the proof! I may have to start baking things for our exec meetings.|2016|6

@VRsenal3D we were discussing and we have decided alcohol does indeed work for <b> and <i>|2016|6

I love #VR & I can show you! Learn about #JavaScript &#VR with my talk from JSConf Budapest: http://t.co/MqnlOr69aI http://t.co/3FWLwbsdgs|2015|6

6 miles is 6 miles too many >.< #ow|2011|8

RT @ActiveReplica: This Week in Constellation 🌌 8.15 - 8.21 https://t.co/22T5CKUvir|2022|8

Eventually, I will re-run my local agent’s sentiment analysis script to score and assign values to my previous Twitter posts, which I expect will be more optimistic on average than the other platforms that I’ve parsed through so far. For many years, I found a lot of joy on Twitter, and I expect that will be reflected.

Going through this old data is – as always – humbling. The boyfriend who turned me on to Twitter and I never spoke again after our breakup in 2011, and our social circles didn’t overlap so I have no idea how he is. Seeing old tweets to him, expressing the delight and love that we had together, was a reminder that my memory of difficult times doesn’t erase the moments where we shared a love of cupcakes and group raids.

Humans are designed to remember negative experiences over positive ones. Our capacity for memory is highly fallible, and recent studies suggest that social media use exacerbates a loss in memory functions. These social media platforms – which provide a carefully curated and structured format for personal, longitudinal data – are playing a role in both preservation and manipulation of the human experience at a species-wide scale. As a result, we’re seeing the real-time impact of ‘post-truth’ politics play out around the globe.

For artificial and machine learning, context is king. Companies building LLMs have slurped up the entirety of the internet to create the world’s most complicated regression models, selling probability as truth. But no matter how much context I share with ChatGPT, it will not know the pain my 15-year-old self went through as I navigated the tensions between high school heartbreak and friendships. It cannot make the connection to my 24-year-old self tweeting about how she loves making art with numbers and bridging that to the joy that 34-year-old me gets from studying Nadieh Bremer’s work and learning R.

Nor do I want it to.

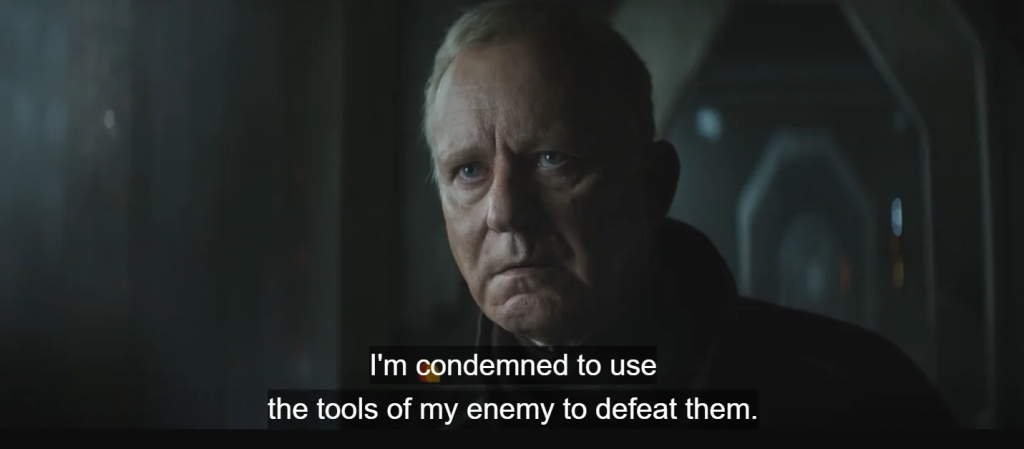

When we explore the original intention of personal computing, the goal was not to abstract away the complexity and capability solely to concentrate power and wealth among the Gates, Bezos, and Zuckerbergs of the world: it was to enable humans to go beyond what their brains alone could accomplish. Yet today, we find ourselves in a society that is entrapped in the algorithmic hellscape that accompanies our surveillance-driven dopamine machine. The narrative surrounding generative AI – that it may destroy us, should it reach sentience – continues to force us down the path that billionaires want us to see as an inevitability. The good news? It’s not working.

It is not the large language model itself, or generative abilities of machine learning broadly, that is creating the socioeconomic conditions we find ourselves in today. It’s the way that those in positions of power are choosing to deploy this technology at the expense of human workers and environment. It’s the consolidation of digital literacy and self-regulation that facilitates larger and larger power/land/capital grabs; it is the disregard for human rights to their work and likeness that is being swept under the rug in favor of pointing to AI itself.

Technology monopolies want to create a false dichotomy: you can either get on board with their flavor of AI, and accept its presence in your life as it creates a further dependency and surveillance loop, or you’re destined to be left behind. They don’t want you to view your data as currency; the opacity of algorithms are designed to keep you confused, frustrated, and scared.

But resistance is building.

Working with data is challenging. Even with a degree in Computer Science, actively learning higher-level applied statistical analysis, wrapping my head around the process of extracting my own data into formats where I can use it and curate it from different sources takes a significant amount of mental energy. This is a project measured in years, not weeks, and it is at times exhausting.

It is hard to look back on how I used to communicate, but it is ultimately going to make me a better person than if I were to pretend I never went through uncomfortable and awkward phases where I was mean to my friends and struggling to understand the world. But the work is local, in the truest sense of the word. I am not asking someone else in another country to read my messages and identify the threads of hurt – and at times, trauma – for extremely low pay and no mental health support.

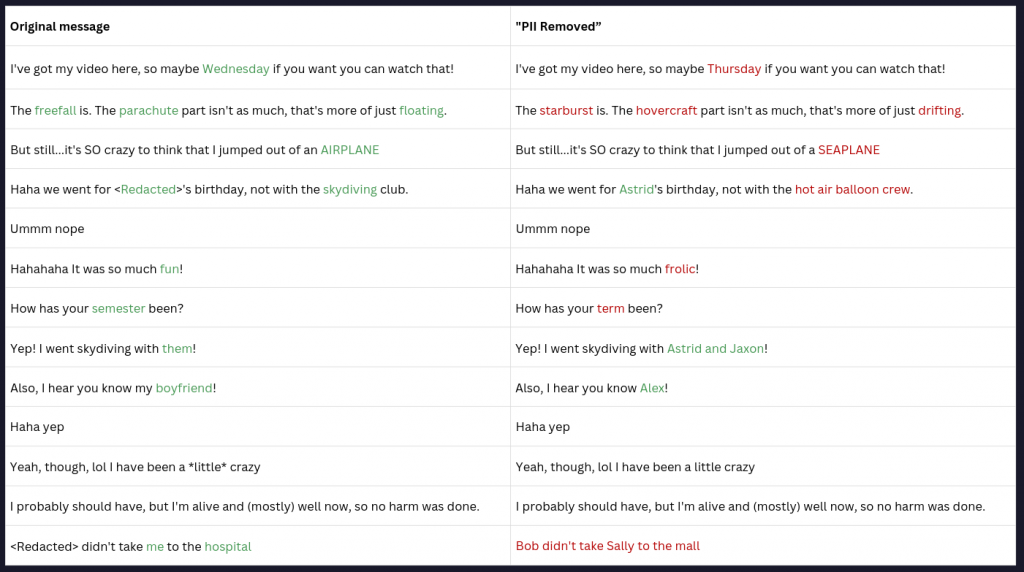

In parallel to my Twitter archive extraction today, I also used a local LLM to try a new experiment on a subset of my messages. From my database, I pulled out all of the messages that I wrote from the age of 16-21, and attempted to strip out the PII from the messages using Ollama. My hope was that I would be able to have a reasonable, semi-synthetic dataset of how my personal communication evolved. Instead, I got an interesting lesson in what LLMs are still quite bad at.

I’ve dubbed one particular area of failure ‘The Azeroth Error’ – the case where the language model became exceptionally bad at contextualizing World of Warcraft separately from my ‘AFK’ life situations. I can imagine a future ‘Azeroth Error Index’ measuring how well a particular model can accurately classify and identify words and situations when in a blended context like a chat thread.

Another area of error was the identification of proper nouns. In my attempted PII cleaning, I found that the model I used (llama3.1:7b) had very high misclassification rates, which resulted in a high level of replacement text:

At the end of the day, we don’t know what tools, platforms, and capabilities will be available to us in the future. Creating this archive gives me the ability to future-proof a wealth of context about who I was – and how that’s shaped me. Doing it locally means that I get to consolidate the sources of information that I’ve been freely sharing online for decades, creating a far more personalized and tailored version of my history than any one platform alone would allow.

And I think that’s neat.